Port Susan Bay

Written by Rebekah Joyal

Port Susan Bay is an estuary in Snohomish County, just a few miles north of Everett. The estuary is fed by the Stillaguamish River, responsible for around 70% of the Puget Sounds estuaries, of which only 30% remain. The Port Susan Bay project was largely spearheaded by The Nature Conservancy, but is traditional land of the Stoluck-wa-mish River Tribe and the Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians. Thousands of Chinook salmon once moved through Port Susan Bay, but these numbers have declined steeply. Salmon are a vital cultural piece of many Pacific Indigenous Tribes. Because the Port Susan Bay area was once farmland, the land is deeply disturbed by humans and consequently many nonnative plants have been introduced.

Working in Port Susan Bay with Mikey’s crew was a project that stuck with me because it was a example of the way restoration work developes over time. A week working on a project does not reflect the entire scope of what happens over the entire length of a projects development and execution. The Port Susan Bay project is fascinating because it was a wetland drained to be farmland; and is being restored to wetland once again.

Port Susan Bay is fed by the Stillaguamish River, resulting in a place where fresh water meets salt water, creating an environment that is vital to spawning salmon’s life cycle. Estuarine environments like Port Susan Bay are places of decay, but this decay supports the life of invertebrates, several salmon species, clams, and many bird species. These brackish estuaries are mecas of life that are vital to the life cycle of many creatures.

As salmon spawn, they need protection as they grow from fries into adult salmon. The intricate lattices of marshland plants provide exactly that; yet when farmed these critical habitats are lost. Chinook salmon need still water where they can feed on bugs that land on the water’s surface and put on the necessary layer of fat before they go out to sea. Wetlands provide this critical still water habitat, and thus are an important goal in restoration. Port Susan Bay has been largely restored as a marsh through manually carving channels in the wetlands, but due to the massive soil disturbance, the wetland has become a massive monoculture of invasive narrow leaf cattail that has hybridized with the native broadleaf cattail.

The monoculture of cattails does not foster an environment in which chinook salmon thrive and as their population numbers dwindles; creating an environment in which they will be able to adapt to living in salt water is of utmost importance. A process known as smolting, in which they feed on bugs that drop from plants hanging over the water, is fostered specifically in these ecosystems.

Creating an abundance of habitat for salmon to spend time in on their way to the ocean ensures that these salmon will have a higher survival rate once they get to the ocean.

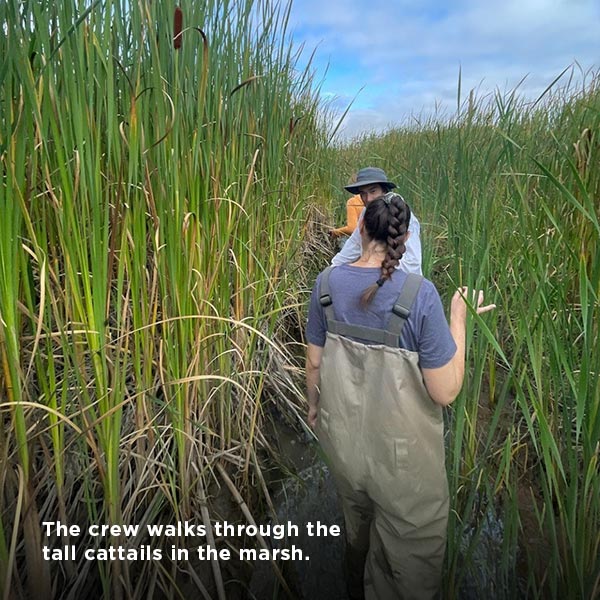

The work we did in Port Susan Bay was only a small portion of the work that is needed to bring the marsh back to the historical productivity as an ecosystem. During our time working at the marsh, we cut invasive cattails and removed the remnants of the cattails to ensure an open soil on which future natives can take hold. We also applied herbicide to the cut cattails to slow their regrowth and allow space for native plants to propagate. The hope is the king tides this upcoming November will aid in clearing space for the native plants to have greater areas of soil on which to grow.

Looking forward into future projects, taking aim specifically at naturalizing Port Susan, it is clear that greater biodiversity needs to be had. Bird species living in the area will help in spreading some of the seeds, nonetheless human introduction of non-hybridized broadleaf cattails would benefit the ecosystem through the addition of a less aggressive growing pattern, which would allow for a more diverse selection of flora to grow.

Continuing work in Port Susan Bay is very important because of the amount of habitat these spaces provide. The Chinook Salmon have seen a massive decline in returning fish populations, which has become increasingly concerning. The removal of salmon habitat in brackish water lowers their survival chances in the open oceans. This concern is compounded when one takes into account salmon are culturally significant to Native American peoples as a historic food source. Salmon are additionally important ecologically as their return to their spawning grounds feed bear and fertilize the ground by bringing ocean nutrients inland. Restoring habitat for these creatures is vital to the ecosystem and to humans as they are culturally relevant for all living in the Pacific North West. My experience in Port Susan Bay allowed me to learn more about these processes and protections firsthand.

Rebekah spent most of her childhood outside, which has inspired her love for learning more about the natural world. Rebekah moved from Berea, Kentucky where she got a degree in Anthropological Archaeology. With a background in organic farming and working on archeological digs, Rebekah understands how human connections to the earth shape culture. As an EarthCorps crew member, Rebekah is excited to be immersed in the nature of Washington and learn from those around her. When she is not digging in the dirt, Rebekah loves baking bread, finding fun swim spots, and biking anywhere she can.